*Author’s note: In the process of analyzing films, I let loose major spoilers.*

Childbirth and pregnancy are by nature nerve-wracking, agonizing experiences. “It takes a lot of pushing and stretching to move a baby the size of a melon through a cervical opening the size of a kidney bean” (Sears, et al, p. 291). Even cesarean sections involve ironically painful injections of anesthetic. Multiple horror films explore monstrous babies and by association the horrors of being pregnant: The Fly (the baby is a giant maggot), The Unborn (possessed by an evil spirit), Dawn of the Dead (a zombie), The Astronaut’s Wife (an alien). In It’s Alive the baby leaves the womb and immediately kills the hospital staff that delivered it, leaving its mother crying, “What’s wrong with my baby?” It’s way too easy to get wrapped up in the fears of something bad happening.

Pregnant women have multiple worries, aggravated by the unreachability of the baby—the closest they can get are glimpses during an ultrasound or a few seconds of listening to a heartbeat, and both require medical personnel to interpret whether they’re normal. Not to mention the weird sensations that accompany pregnancy (especially for a first-time mother), unsure if she’s feeling a kick or only indigestion. (As a fetus, my brother used to stretch his little limbs so hard that he left external bruises on our mother’s stomach.) Pregnancy actually sounds like a horror movie, when you think about it: a small organism attaches itself to someone and feeds on her through her bloodstream. It might make her crave or loathe food, it will probably make her nauseated all day long, and it will definitely distend her stomach to the size of a basketball. Eventually it will either tear its way out or will have to be cut out. It’s basically the chest-burster scene in Alien. Horror films about pregnancy and childbirth often use both of these concepts: the alien nature of the situation, and the uncertainty and anxiety that go along with the process.

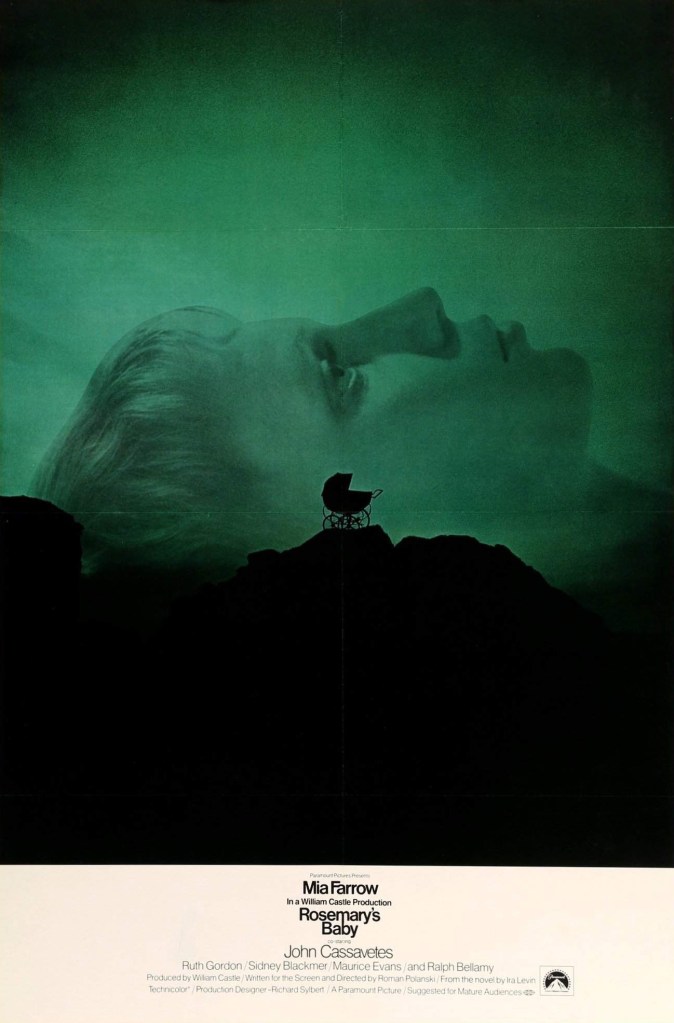

Rosemary’s Baby illustrates this struggle in the frame of an inhuman baby. Rosemary and her husband Guy unwittingly move into an apartment house that’s home to a cult dedicated to bringing about the birth of the antichrist. Guy, having been promised a lucrative acting career, doesn’t hesitate before selling out Rosemary’s body. He’s a master of manipulation from the beginning, duping her into eating a drugged mousse that tastes weird by catering to her urges to please people. While still partially conscious, she’s raped by Satan and impregnated. Afterwards, she’s surrounded by people who claim to be on her side but are really just in it for themselves. She’s pressured into doing what’s supposedly best for the baby, like when cult leader Mrs. Castevet practically force feeds Rosemary a drink that she hates. (Then again, her instincts tell her to eat raw meat, so maybe she’s better off with the drink after all.)

They tell her how she should act and even how to feel. She has sharp pains, and is miserable, but her doctor, who’s in the cult–his first words to her being not to read books or listen to her friends–convinces her that it’s normal. She looks pale and exhausted, with dark circles under her eyes, and she’s losing rather than gaining weight. At times, she’s doubled over in pain. She says, “It hurts so much. I’m afraid the baby’s going to die.” She panics when the pain stops, but then the baby kicks and her fears are temporarily assuaged. When Rosemary’s real friends step in and intervene, Guy blocks them and tries to turn Rosemary against them.

Even when she goes to a second doctor who is not under the influence of the satanists, he takes her story as hysterics and calls Guy to come and get her. He brings Dr. Sapirstein, who warns, “Come with us quietly, Rosemary.” Guy never stops lying to her; in order to raise the baby the way they want, the cult convinces her he died. Guy tells her the whole experience was hysteria. “You had the prepartum crazies,” he says. Rosemary hears her baby crying through the walls, and tracks him down to Roman and Minnie’s apartment. Her maternal instincts come out even more, despite her son’s bestial appearance. (The movie doesn’t show him at all, but the book describes him as having little horns and yellow goat eyes.)

She’s paralyzed in shock until Andy, as she had planned to name him, starts crying. She chastises cult member Laura Louise, “You’re rocking him too fast. That’s why he’s crying.” Roman urges, “Rock him.” Rosemary says, “You’re trying to get me to be his mother.” “Aren’t you his mother?” Roman replies. Once Rosemary gives in and rocks Andy, he stops crying. Looking down at him with a bemused expression, Rosemary almost smiles. He’s won her over.

Mothers are expected to be perfect health machines, or the consequences can be dire. Many fairly innocuous things like tap water, many kinds of fish, caffeine, deli foods, and hot dogs are dangerous to a fetus. There are also multiple necessary precautions like avoiding cat litter, electric blankets, paint, microwaves, and water beds. Researchers have even started leaning in the direction that not only teratogens but also stress can harm the baby, and even future generations: “Research in the new field of epi-genetics shows that a baby’s womb environment can set up a baby for health, or disease, for the rest of her life […] What goes into your mouth, your gut, even possibly your thoughts [italics mine] conceivably could pass into your baby […] So expectant moms, give your grandchildren a healthy start.” (Sears, Sears, Holt, & Snell, 9-13).

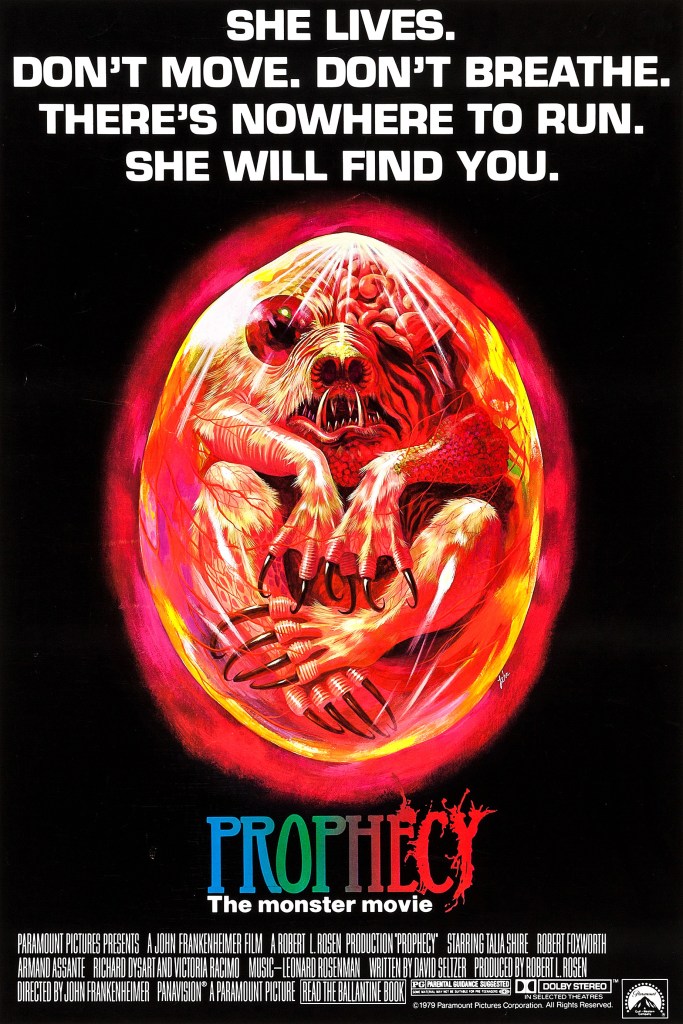

The movie Prophecy is primarily focused on teratogens. Maggie has found out that she’s pregnant but is afraid to tell her husband Robert, because she knows he believes “The world is such a mess, it’s unfair to bring a child into it […] there are three million unwanted children.” A major visual focal point in the film is harm visited upon babies. Robert is a doctor; in his first scene he’s visiting a rundown, predominantly Black neighborhood to treat a baby for rat bites. Crying, his mother says, “I showed it to the [landlord]. He say it was chicken pox. I say to him, ‘There’s rats in here.’ He said, ‘This is chicken pox.’ I said to him, ‘Ain’t no chickens in here. There’s rats in here, and them rats bit my baby.’ You know what he said to me? He said, ‘The rats got to have room to live, too.’ ” Robert asks, “Does he live in this building, your landlord?” “No, sir. He lives in Georgetown. He lives with the rich rats up there.” “I’m gonna have to put your baby in a hospital, and I’m gonna be in touch with your landlord.” “How about putting my landlord in the hospital? That’s what I’d like to do.” A prominent theme in the film is that horrible things are easy to ignore as long as they don’t affect us directly. As Robert tells a colleague, “It’s not the hours, it’s the damn futility. God. You know, I’ll write a report here that no one will read. I’ll file a lawsuit against a landlord that’ll be settled out of court. Send that baby to the hospital for a couple of days, so he can come back here and be eaten by rats again. I feel like I’m banging my head up against a wall. I don’t think anybody’s listening.” Robert and Maggie head to Maine to investigate whether a paper company is poisoning the land and water. Robert finds mercury, which causes the local Native Americans1 living on the land to have deformed and stillborn babies, while the wildlife are mutated in horrible ways—like being born without skin.

John, the leader of a protest by the Native Americans, states, “The environment is us, and it’s being mangled.” He too feels like no one listens. Maggie unknowingly eats a contaminated fish, and she listens in horror as Robert (who still doesn’t know she’s pregnant) expands on the affects of mercury poisoning: “It acts on the nervous system, it destroys the brain […], affecting the fetal development of everything that ingests it […] It is the only mutagen that jumps the placental barrier, concentrating in fetal blood cells, where it adheres to the DNA and corrupts the chromosomes. The ratio of toxin to blood level is 30% higher in the developing fetus than in the host.” She and Robert have to ponder whether they can handle a mutated baby. As Maggie says, “I’m pregnant. And I ate what the mother of those creatures ate. It’s not a nightmare that’s gonna end, it’s just beginning because it’s inside me.” A b-side theme is the power of the maternal instinct. Maggie bitterly concludes, “It’s not a baby anymore”, before ultimately deciding, “I can’t kill it! I wanted a baby.” Robert takes two mutated bear cubs as evidence of the mercury poisoning, and is chased relentlessly by the cubs’ monstrous mother, who kills ancillary characters left and right before Robert finally manages to stab/bludgeon her to death. The film ends with Maggie in a hospital being treated, then cuts to the mother bear roaring angrily. Nature finds a way.

It’s easy to lose one’s sense of self during pregnancy. A woman’s needs become secondary to the fetus; her whole body is altered to accommodate the baby, with her organs literally shifting around, and hormones causing emotional overload. This is a description of a fetal ultrasound from my insurance’s website: “You may need to have a full bladder. A full bladder helps transmit sound waves, and it pushes the intestines out of the way of the uterus. This makes the ultrasound picture clearer. You will not be able to urinate until the test is over. [Yup yup, you gotta fill your bladder as full of water as you can and then have a wand jabbed in your gut for roughly 20 minutes. It’s a blast.] But tell the ultrasound tech if your bladder is so full that you are in pain. [Then you are allowed to pee and then maybe you can drink more water and finish what you started–if you don’t have to reschedule and do that shit all over again.] If an ultrasound is done during the later part of pregnancy, a full bladder may not be needed. The growing fetus will push the intestines out of the way” [italics mine]. “Women face three types of challenges as their bodies begin to adapt to the demands of growing a baby: the physical ones brought about by the enormous hormonal swings of pregnancy; the psychological challenges of changing relationships within the family, and with the world; and the loss of identity many women experience when they realize that they are no longer in control of their bodies or their minds” (Puryear, 30). One example of this is a side effect typically called “pregnancy brain,” or “mommy brain,” which is attributed to new growth in some areas, causing memory lapses and absentmindedness.

The movie Honeymoon depicts a marriage ruined by an unwanted pregnancy and an epic case of mommy brain; the alienness of pregnancy and the intrusive nature of being pregnant are front and center. Bea and Paul are established from the first frame as a happy couple with a romantic back-story. They’re very affectionate and constantly touching. While on their titular honeymoon they can’t keep their hands off of each other. In nearly every scene they’re either having sex or making innuendos.

After a particularly vigorous bout of lovemaking, Paul jokes about how Bea needs to rest her womb. She reacts with dismay, and they discuss how neither of them are ready for children. Paul concludes, “We got plenty of time to talk about your womb and other married-people things. Right now, I think we should just be on our honeymoon.” The cabin they’re staying in was Bea’s from her childhood, and is full of nostalgic memories for her. The two act childish on occasion, like when they have a foot race to a restaurant, with Paul shouting, “Last one there is a rotten egg!” They’re happy; Bea in particular is often smiling and happy and goofy. All of this changes when Bea is lured into the woods by extraterrestrials and implanted with an alien creature. Paul finds her wandering outside, naked, and she screams when he touches her. The act of conception is exaggerated into a terrifying, intrusive experience. Paul later finds Bea’s nightgown in the woods, full of holes and covered with a slippery substance.

She claims that she can’t remember what happened, but she becomes less cheery and bubbly and is still jumpy every time Paul touches her. Bea refuses to have sex with him and is in denial about what happened. Paul finds her rehearsing excuses not to be intimate: “My stomach just feels icky.” Not only is she loath to be touched, her behavior is suddenly erratic. She forgets to batter bread for French toast, and she forgets common words like suitcase, saying “clothes box,” or instead of saying she’ll nap, she says, “I think I’m just gonna go take a sleep.” Indeed, Bea is often tired, mentioning constantly how fatigued she is. She explains her condition away by saying “I’m just feeling a little funny.” Another of her odd behaviors is writing details of her life in a journal, including her name, address, birthday, and favorite color. Bea has an extreme case of pregnancy brain as the alien influence causes her to forget important details about herself—she is losing her identity. As she says, “My body is here, but I’m leaving. They’re taking everything. They’re–they’re taking me. Bea. They’re taking Bea.” Paul is frequently saying how much Bea has changed recently: “You feel different.” He also states, “I just want things to be normal. I just want us to be us […] Where is my wife? […] You look like her, but you’re not her.” As Bea says later, in a chilling twist on a quote that was previously about Paul but becomes about her monstrous offspring, “Before I was alone, but now I’m not.”

The time right after giving birth can be particularly brutal. For the first three months or so (or more, if the baby’s an asshole), babies need to eat every three hours at least, around the clock. Nursing especially is a taxing job. “Although breast-feeding is in many ways a wonderful thing, it means the mother gives up all sense of personal space. When your baby is hungry and ready to eat, for the most part it’s your job to unbutton your shirt and provide the food” (Puryear, 124). As my friend Paula put it, she and her infant son were “attached at the nip.” In the hospital with Layla, I once fed her for three hours straight; the nurse assured me that sometimes babies are full but are comforted by the sensation of nursing. This connection begins sooner and sooner after birth. When Layla was born I had about an hour to myself to regain the feeling in my legs after my cesarean, but my second child Orion was thrust into my arms the moment he was clean, with instructions to feed him. “Here’s the reality: the days, weeks, and months after childbirth can be overwhelmingly difficult, and having a baby marks the beginning of one of the biggest life changes you will ever go through. You’re recovering from the physical trauma of giving birth, your hormones have gone haywire, you’re sleep deprived, and now you are completely responsible for every aspect of another human life” (Venis, 1-2).

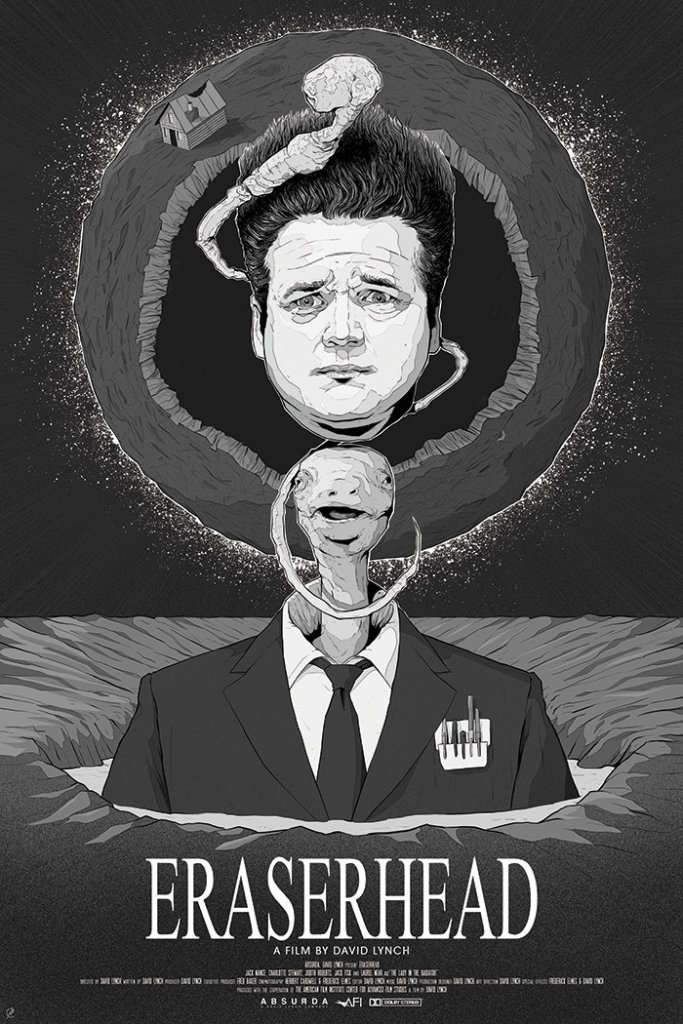

The movie Eraserhead portrays the trials and tribulations of having a newborn, with none of the pleasure involved in the process. The protagonist, Henry, is confronted by his girlfriend Mary’s mother, who claims Mary had his baby, despite Mary’s protesting “They’re still not sure it is a baby.” Mary’s mother threatens, “You’re in very bad trouble if you don’t cooperate […] After the two of you are married, which should be very soon, you can pick the baby up.” Meanwhile Mary is sobbing hysterically, and Henry has a panic attack and resulting nosebleed, literally gagging at the situation. The infant, which is rumored to have been constructed by the filmmakers from a cow fetus, looks like exactly that. It also has strange growths and no limbs—only a head and a bandaged torso.

It not only refuses to eat what it’s fed, it spits the food back in Mary’s face. The pair are neglectful parents; Henry comes home and doesn’t even glance at it, and both of them tend to keep it lying on a table without picking it up, even when it cries. It keeps the couple awake with its unnatural wailing. Mary snaps, yelling: “I can’t stand it. I’m going home.” Henry answers, “What are you talking about?” “I can’t even sleep. I’m losing my mind. You’re on vacation now, you can take care of it for a night!” “Well, you’ll come back tomorrow?” “All I need is a decent night’s sleep!” “Why don’t you just stay home?” “I’ll do what I wanna do! And you better take real good care of things while I’m gone.” She returns home once to sleep and afterward disappears for the rest of the movie. Henry sort of takes care of things, staying with the baby when it panics at the prospect of his leaving the apartment and gently taking its temperature when it’s sick, but he doesn’t grasp the concept that babies need watching constantly, especially when the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall wants to make out. In the end, while cutting off its bandages, Henry stabs the baby. It dies after turning to an oatmeal-like mush, and Henry lives happily ever after with a new love interest. Many of the visual images invoke anxiety about parenting. In the opening sequence, Henry is shown looking worried, and then the baby floats out of his mouth, umbilical cord and all. In one scene, his head pops off and is replaced with that of the baby’s, crying.

When Henry visits Mary’s house, there is a mother dog with squealing pups all trying to nurse at once. Henry has a vision of his new love interest, the Lady in the Radiator, stepping on and crushing miniature versions of the baby, a segment which must be seen to be believed:

1 Well, at least they used some actual Indians, rather than whities in brown-face, though the main guy is actually Italian.

Lucy J. Puryear. (2007). Understanding Your Moods When You’re Expecting: Emotions, Mental Health, and Happiness—Before, During, and After Pregnancy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

William Sears, Martha Sears, Linda Holt, and B.J. Snell. (2013). The Healthy Pregnancy Book: Month by Month, Everything You Need to Know from America’s Baby Experts. NY: Little, Brown and Company.

Venis, Joyce A., and Suzanne McCloskey. Postpartum Depression Demystified. NY: Marlowe and Company, 2007.